Before King uttered “I have a dream,” there were others “” a grandfather and a father “” who instilled great dreams in him and had great dreams for him.

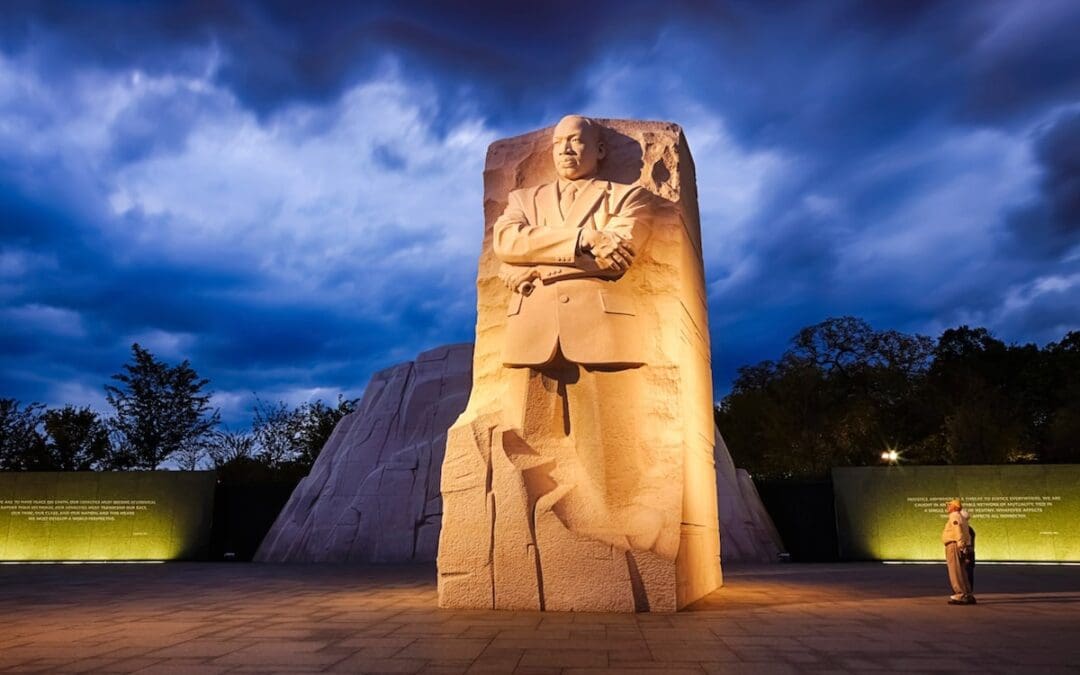

A few years ago, I spent some vacation time in Atlanta with my family. While there, I made a pilgrimage to the Ebenezer Baptist Church, the home church of Martin Luther King, a dreamer of heroic proportions who inspired the world. In addition to being a place of worship, Ebenezer Baptist Church is now a historic landmark and teaching facility for those interested in learning more about King and the civil rights movement.

A few years ago, I spent some vacation time in Atlanta with my family. While there, I made a pilgrimage to the Ebenezer Baptist Church, the home church of Martin Luther King, a dreamer of heroic proportions who inspired the world. In addition to being a place of worship, Ebenezer Baptist Church is now a historic landmark and teaching facility for those interested in learning more about King and the civil rights movement.

As I entered, the simple grandeur of the place struck me. The well-worn pews stood proudly in the immaculate sanctuary. Speakers played recordings of some of King’s most famous speeches, and I immediately returned to 1965. I heard the applause. I joined the chorus of “Amens.” I was really there, part of the struggle “¦ part of that great movement.

I was snatched back to the present, however, when the National Park ranger who was assigned to the church lowered the volume on the speakers so he could give prepared remarks. I must admit I became a bit annoyed at this point, thinking, “What can this guy tell me about Dr. King that I don’t already know? I am a black child of the ’60s. I remember when he was shot. I read about him in school. I have seen countless documentaries on the civil rights movement.”

The learned ranger surprised me. He did not start his presentation by talking about King or the famous civil rights marches or even Ebenezer Baptist Church. He started by pointing to two stained-glass windows, which bore images of King’s maternal grandfather, the Rev. A.D. Williams, and his father, the Rev. Martin Luther King Sr.

I learned that Mr. Williams, who served as the pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church for 37 years, was an eloquent speaker and noted local political activist who contributed his efforts “” and meeting space in his church “” to a number of organizations dedicated to the education and social advancement of black citizens.

On Thanksgiving Day 1926, Mr. Williams’ daughter Alberta married Martin Luther King Sr., a young minister. The couple moved into an upstairs room in Mr. Williams’ home. King Sr. worked weekdays, preached Sundays, and spent evenings at Morehouse College studying toward his divinity degree.

Mr. Williams mentored King Sr., and upon Mr. Williams’ death in 1931, King Sr., or “Daddy King” as he was affectionately known, took over as pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church. Like his father-in-law, Daddy King’s ministry focused distinctly on social justice and he sought to engage and empower all black citizens in his community.

Daddy King was an involved father who always stressed the importance of education to his children. In fact, he once said that even before King Jr. could read, “He kept books around him; he just liked the idea of having them.” It’s no surprise that King Jr. graduated from Morehouse College at 19, and before turning 27 he had earned two more degrees, a bachelor of divinity from Crozer Theological Seminary and a doctorate in theology from Boston University.

Five-year-old King Jr. formally joined his father’s church in 1934. Young Martin preached his first sermon under the watchful eye of his father at age 17 and soon joined him as co-pastor. In 1957, Ebenezer Baptist Church held an organizational meeting for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). King became the first president of the SCLC, an important organization at the forefront of the civil rights movement. And the rest, as they say, is history.

As the park ranger closed his presentation, it struck me that generations before King uttered the now immortal words, “I have a dream,” there were others “” a grandfather and a father “” who instilled great dreams in him and had great dreams for him. He was the product of a legacy “¦ a fatherhood legacy.

(Portions of this post originally appeared in a February 1, 2009 Washington Times article I wrote titled: King’s Legacy Begins with His Grandfather.)